IT’S ABOUT THANKSGIVING

By Mona Sides-Smith

Over the gravel and through the weeds, to Grandmother’s house we went. It was Thanksgiving. It could have been any holiday. Or any Sunday. Or any day, for that matter. It was where we went when I was twelve years old — give-or-take a few years. When I was ten years old, we moved from the farm to a coal mining settlement in Southern Illinois, to be near my grandparents when my father was drafted to go off and get himself bombed-blasted up against a tree in the Belgium Bulge during World War II. He survived, physically anyway – but that’s another story. This story is about Thanksgiving, beyond the weeds, at Grandmother’s House.

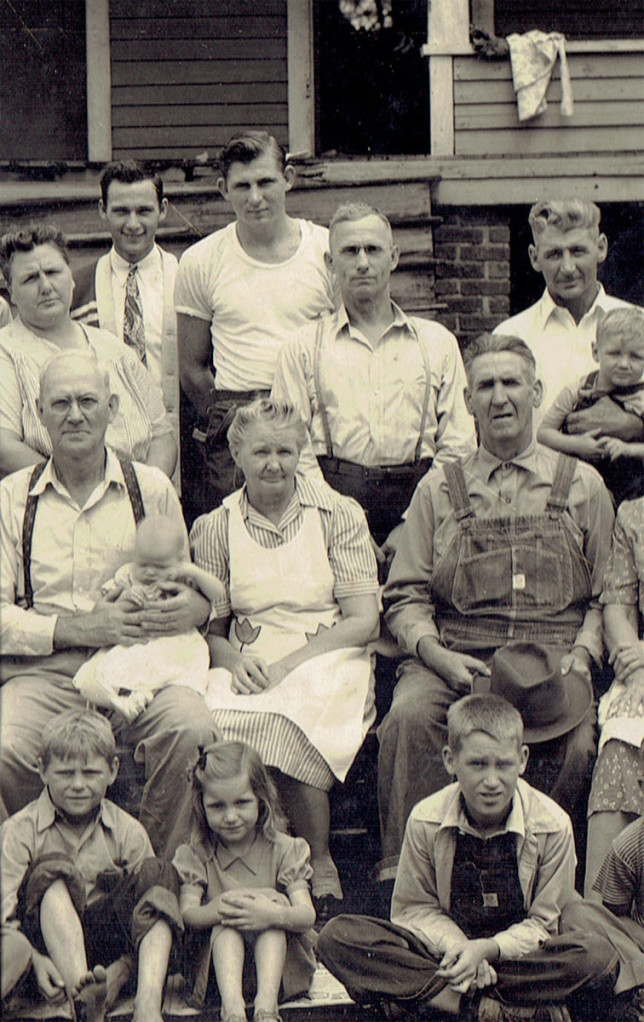

There would be a mob of people there, that day and almost any holiday or Sunday. Twenty-five people, not an unusual number. We would be a motley collection of farm kids in bib overalls, coal miners and other assorted people of all ages. About half of us were Native American or some mixture of Native American, Middle European immigrants and Southern Illinois folks born-and-raised somewhere not far from the Mississippi River between Cairo and East St. Louis. Grandmother’s house (and ours) was in Ezra according to a map, Pershing according to the post office and was generally referred to by folks in and around Ezra/Pershing as Fifteen. Old Ben Number Fifteen was the soft coal mine that overlooked the mining dusty patch settlement of about a hundred families. Probably half of the households were English speaking. The rest were a mixture of Polish, German, Russian, Czechoslovakian, Yugoslavian, Lithuanian and an occasional Native American blend. This was Thanksgiving Day.

People brought food and my grandmother cooked food. Many of the participants had ancestors who originally came from Holland. The Zuider Zee, I have been told. They were the first Lutherans into the United States, having landed in what is now North Carolina. When they were able, the hopeful pioneers began meandering west until they came to what we now call the Mississippi River. The family story is that they decided to settle there. My story is that the women, having recently been hauled across the Ohio River, in make-shift boats full of their damp stuff and damper complaining children, said, not only “No” but “Hell no, we’re not crossing another river.” So the men acquiesced, divided up the land and built a Lutheran Church, which still stands, for weddings and other special occasions, in Dongola, Illinois. The wandering pioneers were managed and preached at by Tenth Great Grandfather Zachariah Lyerla, whose tombstone (provided a few generations ago) broods over the church on a daily basis. The men without wives, mixed and mingled with the natives, if you get my drift, and produced the first half-Indians to help them hack out logs for houses and to plant and grow foodstuffs.

The Grandma and Grandpa of my childhood would start the Thanksgiving Day by ambushing several chickens, grasping them by the head and, with a quick flick of the wrist, beheading them. That was the part I liked to watch as a kid; it grosses me out now to think about it. Then the birds were dipped in pre-prepared boiling water in an iron pot over a fire in the back yard. This was for the purpose of loosening the feathers. There was an art to it – dip them long enough to release the feathers and not cook the skin. Then came the chicken plucking: The small feathers were saved in cotton feed sacks so pillows and feather beds could be made after we had eaten enough of the unfortunate birds. The larger wing feathers were thrown away. I tried to avoid that plucking part by hiding in the barn or going to the outhouse.

The rest of the morning was a mix of activity with kids running in all directions, women sweating over cooking pots and fogging the air with flour while the men were sitting in chairs in the yard swapping tales, laughing and lying to each other. The most memorable one for me was the holiday morning my cousin, Maxine, and I reached up from outside and each stole a pumpkin pie from the kitchen window sill where they were cooling. We took the pies upstairs and had a contest to see which of us could eat a whole pie the fastest. I don’t remember who won, but I do remember that we ate the pies and that we both lost the contest. It is a quirk of physics that a whole pumpkin is not likely to stay down in the stomach of an adolescent girl. Ours didn’t, but the rest of that particular Thanksgiving Day is a blur.

At noon, give-or-take a half hour, the gorging began.

The men were summonsed and seated around the large round oak table in Grandma’s kitchen. Well, the table actually was made oval for holidays with at least two foot-wide leaves that were inserted in the stretched out middle of the table for the occasion. The women continued to sweat, wiping their furrowed brows with their aprons, while replenishing the bowls and platters of steaming food in front of the diners until the last of the men leaned back in his chair, patted or rubbed his distended mid-section, then scooted his chair back, chose a toothpick from the container already provided on the table and returned to the yard, much subdued to doze, chew the toothpick or some tobacco, and, tell or re-tell some stories from other similar days.

The children then were corralled, the worst of the dirt removed from their hands and faces, before they were seated in the chairs recently vacated by the repleted men. I think the requirement was that the male members of the family had reached eighteen years or older to be deemed men. Children ranged from seventeen to highchair age and were both male and female. This second seating of hungry growing humans proceeded to eat, spill or throw large amounts of what remained eatable. The thing that held the women slightly back from the brink of insanity was that kids though loud are quick eaters when they belly-up to their plates. The bedlam soon ended and the diverse next generation left the building.

What was left of the women were last to eat; they found whatever eating utensils remained in a fairly usable condition and slid their exhausted body onto sticky chairs and looked with bleary eyes at whatever remained of the now cold, congealed and picked over food. Chicken wings, cold potatoes and raw onions ranked high. They rested, nibbled, shared family failures and accomplishments, caught up on the gossip, bragged, and shared secrets.

Then the women sighed, assessed the damage and began the struggle of bringing the kitchen and its equipment back into order. Any teenage girls who could be found were pressed into service to help with the washing and drying of the dishes. No men or boys ever were asked to help. In my memory, neither man nor boy ever volunteered.

The day ended with the women in the living room, quilting, piecing quilts, crocheting or just rocking until the men, one at a time, announced that it was time to go home. Then individual families were sorted out and sent or carried to the collected wagons or cars, except for those of us who walked through the weeds and over the gravel to home.

Thank God for those days and thank God things are better now. Or, are they?

Your Thanksgiving story brought back so many memories, mostly good. Thanks for sharing!