Some Southern Boys of Summer

by Gary Wright

“Baseball is like church. Many attend, few understand.”

—Leo Durocher

Baseball is said by many to be the best sport ever invented. That is debatable today, but in yesteryear, it far surpassed every other sport in America—including football and soccer—in popularity. Those who played the game were known as the ‘Boys of Summer,’ for the long summers saw fans following their favorite teams. Throughout the United States everyone followed their favorite team, whether the New York Yankees, the Brooklyn Dodgers, the St. Louis Browns, or the Cincinnati Red Stockings in the major leagues; or in the minor leagues: the Durham Bulls, the Toledo Mud Hens, the New Orleans Baby Cakes, or the Mobile Bay Bears.

Throughout the Southland, America’s past-time saw tens of thousands pouring into stadiums around the country daily, while millions were glued to their radios, each cheering on their adopted ‘Boys of Summer.’ Though the game was invented elsewhere, it took like a duck to a June bug in the Southern part of America. Hard work on ranches, farms, coal mines and the forests made Southern youth hard with muscle and strong in spirit. Naturally, many found their way into uniforms of semi-pro and the big leagues of baseball. Here are accounts of a few of our Southern Boys of Summer.

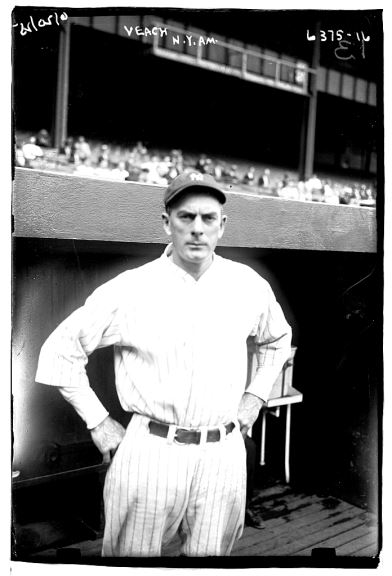

Bobby Veach

Robert Hayes Veach was born in Island, Kentucky, in 1888. His father was a coal miner, and Veach also began working in the coal mine as a boy. Veach recalled, “I started as a miner when I was 14 years old and worked at it in the winters, long after I was earning money as a player.” At age 17, Veach began playing semi-pro baseball. Veach played pro ball for 13 years and had a pretty good record both offensively and defensively, finishing second to Ty Cobb in RBI’s one year.

Bobby Veach accomplished a couple of noteworthy feats. On June 9, 1916, when Veach played for the Detroit Tigers, he scored a run to end Pitcher Babe Ruth’s scoreless innings streak at 25 when Ruth was playing for the Boston Red Sox.

In May 1925, the Red Sox traded Veach to the New York Yankees. Veach played 56 games for the Yankees, batting .353 with a .474 slugging percentage. On August 9, 1925, in his final season, while Veach and Ruth were teammates for the Yankees, he became the only player to pinch-hit for Babe Ruth after Babe switched from a pitcher to an outfielder. That day Babe complained that he was not feeling too well for his final turn at bat, so the manager elected to pull him and let Veach bat for him. Veach singled, and the Yankees won, then Veach went in to play center field, and Ruth went to the showers. The Chicago Tribune reported the next day, “The fans were treated to the unusual spectacle of His Royal Highness being yanked for a pinch-hitter.”

Just seven days before Veach batted for Ruth, a pinch-hitter was used for Lou Gehrig. Imagine! Pinch-hitters for both Ruth and Gehrig within a week!

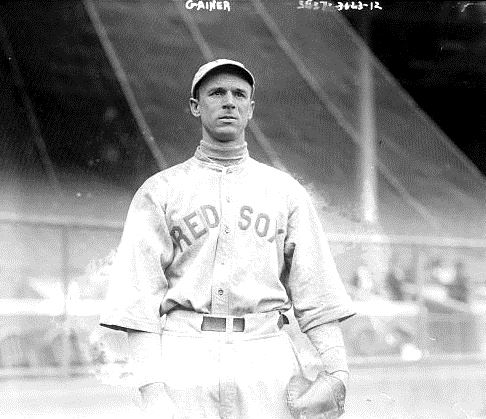

Del Gainer

Dellos Clinton Gainer, nicknamed “Sheriff,” was born in Montrose, West Virginia, in 1886. He played a short, solid, though not overly impressive, career. In the 14th inning of Game two of the 1916 World Series, he had a pinch-hit single to drive in the winning run to end the second longest game in World Series history and win the game for pitcher Babe Ruth. In the 1915 and 1916 World Series, Gainer hit a combined .500. Gainer also belongs to that heady group of people who actually pinch-hit for Babe Ruth, though while Ruth was still a pitcher.

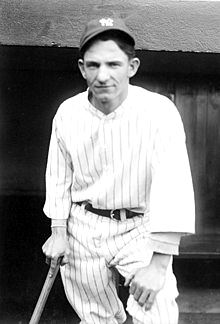

Pee Wee Wanninger

Paul Louis Wanninger was a backup shortstop in Major League Baseball for the New York Yankees (1925), Boston Red Sox (1927), and Cincinnati Reds. A native of Birmingham, Alabama, Wanninger was granted the moniker “Pee Wee” for his diminutive size. He is best known as the player who ended one consecutive-game streak and helped start another. As a rookie, he replaced Everett Scott at shortstop for the Yankees on May 5, 1925, to end Scott’s then major league record of 1,307 consecutive games. On June 1, 1925, Lou Gehrig started his famous 2,130 game consecutive streak when he pinch-hit for Wanninger. For the season, Wanninger had a .247 average in a career-high 117 games.

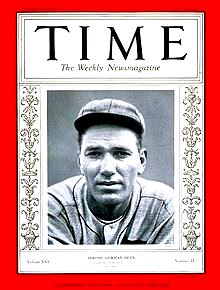

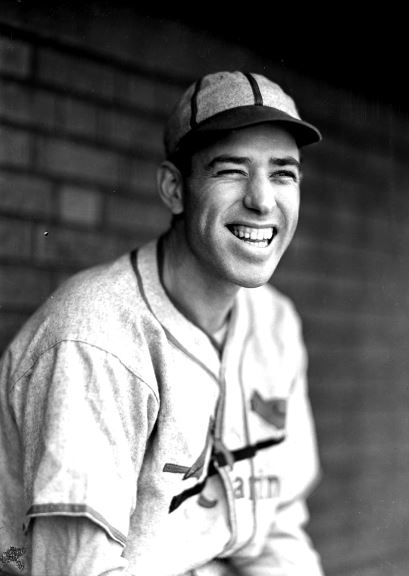

Born on January 16, 1910, in Lucas, Ark., Jerome Herman Dean attended public school only through second grade. His colorful personality and eccentric behavior earned him the nickname “Dizzy.” His natural athletic abilities earned him a spot in the major leagues in 1930. Playing principally for the St. Louis Cardinals, he worked his way up the ladder to become one of the greatest.

Dizzy Dean

The Gas House Gang was the southernmost and westernmost team in the major leagues at the time, and became “America’s Team.” Team members, particularly Southerners such as Diz and his brother, Daffy (Paul) and Pepper Martin, became folk heroes deep in the American Depression. Their supporters saw these guys as extensions of themselves: dirty, hustling and hard-working as opposed the arrogant, highly paid New York Yankees whom everybody outside of New York hated.

Paul Dean

Old Diz was the Ace of the Gas House Gang. Always colorful in speech and braggadocious in manner, in 1934, Old Diz predicted that “Me and Paul are gonna win 45 games next year.” That was an ‘unheard of’ brag, even for Old Diz. Next year, though, the Gas House Gang won the National League pennant and went on to win the World Series. Along the way, the Dean brothers won a total of 49 games that year.

On September 21, 1934, Dizzy pitched a 3-hit shutout against the Brooklyn Dodgers, and Paul went on to pitch a no-hit shutout against them in the second game of a double-header. Later on, in the locker room Diz was overheard to say, “Paul, If’n I’d a knowed you wuz gonna pitch a no-hitter, I’d a’pitched one, too.” On May 5, 1937, he bet he could strike out Vince DiMaggio four times in the game. He struck him out his first three at-bats, but when DiMaggio hit a popup behind the plate at his fourth at-bat, Dean screamed at his catcher, “Drop it! Drop it!” The catcher dropped the foul pop-up, and Dean struck out DiMaggio on the next pitch, winning the bet. When asked about his usual bragging, Dizzy replied, “If’n you kin do it, it ain’t bragging.”

It seems that good old Southern boys always are on center stage or in the background whenever history is made, whenever a heart needs to be wooed, or when there is something really great that needs to be achieved. The ‘Boys of Summer’ spend their lives living out their fantasies of boyhood dreams.

Bobby Veach image: Wikipedia, Del Gainer image: Wikipedia, Pee Wee Wanninger image: Wikipedia, Dizzy Dean image: en.wikipedia, Paul Dean image: Society for American Baseball Research