The Company Store

by Gary Wright

“Saint Peter, don’t you call me ‘cause I can’t go;

I owe my soul to the company store.”

— Merle Travis, ‘Sixteen Tons’

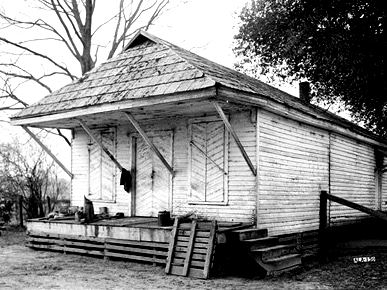

The ‘Company Store’ was probably one of the most vilified institutions in all of recent American history. Though not an exclusive Southern idea, it became much more widespread here amongst the poor, under-educated, desperate, working class. With the abolition of slavery following the Civil War, the newly freed workers were no longer provided housing, food, or services. In the rural South, cotton plantations, for example, began to provide housing, groceries, and a host of other services to its agricultural workers at a cost, often exorbitant. Many times the workers could purchase on credit, but they were compelled to remain on the plantation until that debt was satisfied, resulting in another kind of involuntary servitude called ‘debt slavery.’

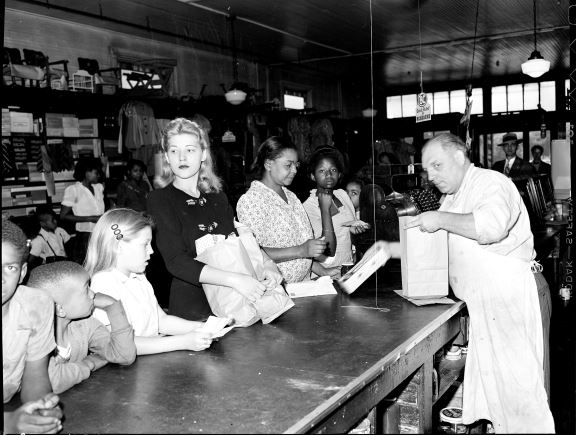

Going by various names in mill towns, mill villages, factory towns, and plantations, a ‘company store’ was a retail store that sold a limited range of food, clothing, and daily necessities to employees of a company. It was typical of company towns in remote areas where virtually everyone was employed by one firm. In a company town, the housing, the retail store, the hospital, barber and beauty shops, and practically everything else was owned by the company. Some independent stores may have been allowed but only those which the ‘company’ could not provide, and, they had to obey ‘company’ regulations.

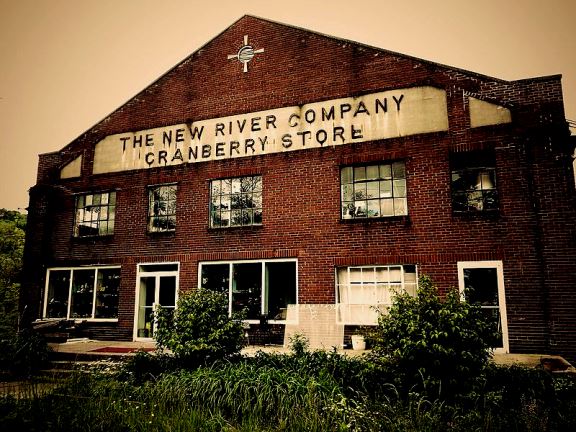

Coal mining town company store, Cranberry, West Virginia

Coal mining town company store, Cranberry, West Virginia

Settings included cotton plantations, lumber camps, sawmills, loom mills, fabric mills, and coal mines; virtually anywhere a large workforce was needed in a relatively small area. These stores could thrive wherever a local population was dependent on an industry dominant in the area. The local workers were restricted by the distance to any competitive ‘store’ so the workers were expected to buy only from the company store as part of their job requirement. Since there was little or no competition, quality was often below standard, variety limited, and prices high. The company store, literally, had a captive audience.

Many such stores would not accept cash money or barter; only tender generated by the ‘company town’ owner. It took the form of store pay (wages paid only as credit) and scrip wages (play money redeemable only by the company.) This system intensified the dependence of the workers and their families on employers. If company stores lacked the items that customers wanted, they had no alternative but to do without, for there was no competition within the confines of the work area, and it was usually a long distance to any competitor.

Here is an apt description by a correspondent from Star Light City, Arkansas “A farmer comes to my door selling produce that I need at a price of thirty cents. He also wants to buy something out of the store and would willingly swap and pay any difference. The ‘company store’ will not let him deal directly with me but he must go through the company store. He is obliged to sell his produce to the company store, and I am forced to pay the company store sixty cents for the article I could have bought for thirty cents. . . .”

If an industry is so big or the area is so completely isolated, then the company store would often encompass the entire living areas, and it became a ‘company town.’ Chickasaw, Alabama was one such town which was dominated by the Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation. Building many of the American warships which helped win the war, it had a population of over 10,000 during the height of WWII but declined soon afterward. Bogalusa, Louisiana’s Great Southern Lumber Co., controlled more than 100,000 acres of virgin pine forest in 1900. Sugar Land, Texas, once owned and run by the Imperial Sugar Company, was a ‘company town’ before it more recently transformed into an upscale suburb of Houston.

Company towns often housed laborers in fenced-in or guarded areas, with the excuse that they were “protecting” laborers from unscrupulous ‘peddlers,’ thieves, riff-raff, and other nefarious outsiders. In the South, free laborers and convict laborers were often housed in the same spaces and suffered equally terrible mistreatment.

If the owning company cut back or went out of business, the economic effect on the company town was devastating, forcing people to uproot and move to jobs elsewhere. The Roosevelt Administration’s New Deal dealt the final blow to end American company towns in the early 1940s by raising minimum wages, encouraging industrial self-governance, and pushing for the owners of company towns to “consider the question of plans for eventual employee ownership of homes.” To a lesser extent, the New Deal also reduced the need for employee housing by transforming housing finance to a lower-interest, lower-deposit system making home ownership more accessible to the working class, especially to the war veterans.

The abuses of the company towns aided in the formation and early popularity of labor unions. The leases for company houses that miners rented to a certain extent governed property rights in these company towns. These leases were also something like “tied” contracts, in that miners rented their homes so long as they were employed by the company, or at least, had a good relationship with it. Leases generally allowed for a quick termination, usually five days’ notice. Many leases prevented non-employees from living in or trespassing on company housing. In some leases, companies reserved the right of entry into the property and the right to make and enforce regulations on the roads leading into the property. This effectively circumvented the 4th amendment’s ban against unlawful search and seizure.

These rights were commonly enforced during strikes when strikers were evicted from their homes. Sometimes, mine owners prevented peddlers or deliveries from independent stores from entering the towns or even company property. A practice that seemed to be more common early on was requiring workers to purchase supplies at the company store.

Mostly, the ‘company store’ is a relic of a past century; a way of life that, thank God, has been bypassed by the advent of modern ethics, morality, and federal laws. We have gone from an era when ‘them what has, gets’ to a more humane existence of the rule of law and the value of kindness and fairness. We can only hope that we have learned valuable lessons from that journey through the sad, forlorn stage of greed and viscous preying on our fellow-man. Hope for the future is what drives ever onward the spirit of humankind. Only adequately enacted laws born out of a sense of fair play and enforced evenly by moderate persons, can ever hold in check the inherent vices of humankind – greed, cruelty, and evilness.

All images from Wikimedia Commons

Another good one, Gary. How true, how sad. Same kind of corporate “spirit” exists today in board rooms giving us such “treats” as the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe. Social and technological irresponsibility flavored with a generous dose of greed. (Will the “magic” never end?) Joe Goodell

Thanks, Joe. It seems that evil is always with us. It just takes different forms and shapes from one era to the next.