Pilgrim in a Racist Land

By J. Randall O’Brien,

Professor and Chair Department of Religion

Baylor University, Waco, TX

2000

The story did not begin with me. And long after I am gone, the story will journey on into the ages. But the caravan did come by here. And I climbed aboard.

Ohhh, dat Gospel train’s a comin’

I hear dat whistle blowin’

Yassuh, dat Gospel train’s a comin’

Gonna ride it t’glory.

The Gospel was the hope of African-Americans in the segregated South when I was growing up in the 1950s and 1960s in Mississippi. They looked forward to the day when that “Gospel Train” would spring their sweet escape from a racist “hell on earth” and land them in the celestial bliss of a peaceful, just, eternal heaven. Some of us Whites dreamed too.

I reckon all who climb aboard God’s Freedom Train understand that the train departs from Egypt always and journeys long through the wilderness before arriving in the Promised Land. Six years after my birth in 1949, the United States Supreme Court handed down an historic decision in the Brown v. Board of Education case on Monday May 17, 1954, ruling that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. In response to the Supreme Court’s decision, Thomas P. Brady (Circuit Court Judge of the 14th District of Mississippi) published a book entitled Black Monday, in which he wrote, “The Negro purposes to breed up his inferior intellect and whiten his skin and ‘blow out the light’ in the White man’s brain and muddy his skin.” Continuing his tirade the racist Judge hissed,

“You can dress a chimpanzee, housebreak him, and teach him to use a knife and fork, but it will take countless generations of evolutionary development, if ever, before you can convince him that a caterpillar or a cockroach is not a delicacy. Likewise the social, economic, and religious preferences of the Negro remain close to the caterpillar and the cockroach.”

In 1963, Judge Brady was awarded a seat on the bench of the Mississippi Supreme Court.

Within two months of the Brown v. Board of Education decision the White Citizen’s Council (which came to be known as “the white collar Klan,” or “the reading and writing Klan”) was formed on July 11, 1954, in Indianola, Mississippi. Two years later the Mississippi Legislature established The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission to maintain segregation. How vividly I recall the “Freedom Rides” undertaken by Black and White activists in 1961, who dared to travel on Trailways and Greyhound buses from Washington D.C. to New Orleans, Louisiana for the sole purpose of testing federal integration laws in bus stations throughout the South. I was eleven years old when the “Freedom Riders” or “Friction Riders” as they were called in the Jackson, Mississippi press, were severely beaten in Jackson and in my hometown of McComb, Mississippi.

The first direct action for integration in Mississippi by Mississippians occurred in my hometown on August 26, 1961, when two local young African-American men, Elmer Hayes and Hollis Watkins, sat-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter. For their trouble they were harassed, arrested, and jailed for 30 days. Four days later, another sit-in took place at the bus station in McComb. Two African-American high school students, Brenda Travis and Isaac Lewis, were jailed for 28 days. Soon thereafter, on October 4, 120 African-American high school students, including Brenda Travis, marched through the streets of McComb to the steps of City Hall. The teen-age Miss Travis was sent away to Reform School for one year.

On September 30, 1962, riots broke out at the University of Mississippi when James Meredith became the first African-American student to enroll at the school. Two persons were killed in the melee and 60 U.S. Marshals were injured. Less than one year later, on June 11, 1963, NAACP Field Secretary in Mississippi, Medgar Evers, was murdered in the driveway of his home in Jackson, shot in the back with a high-powered rifle fired by Byron de la Beckwith of the White Citizen’s Council. The long, hot summer of 1964 lay just around the corner.

The Mississippi Freedom Summer Project of 1964 was a well-coordinated civil rights campaign, which brought to the State hundreds of college student volunteers and other civil rights activists from the North and California to work for racial equality. More than 200 volunteers came to Mississippi on June 20 to establish Freedom Voter Registration, Freedom Schools, and Freedom Medical and Legal Clinics. By June 21 three of the civil rights workers had disappeared. The bodies of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman were found August 4 outside Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Civil rights workers and Mississippi African-Americans suffered horribly in the long, hot summer of 1964. Included in the litany of evils suffered by the innocent were 1,000 arrests, 80 beatings, 35 shootings, 35 church bombings, 30 home bombings, and 6 murders. The list may not even be complete since it includes only crimes that were reported!

My hometown of McComb, located in Pike County in Southwest Mississippi, became known internationally in 1964 as “The Dynamite Capitol of the World” for its 20 acts of violence and 16 bombings of churches and homes in defiance of civil rights advances. Is it any wonder Martin Luther King, Jr. described to United States Attorney General Robert Kennedy the evil in McComb as a “Reign of Terror?”

Shame covered the city like dirty smog. Our churches fell silent; our preachers developed laryngitis. The body of Christ looked nothing at all like Jesus. No tables of racism were overturned in the temple. No ministerial anger cried out against bigotry, hatred, or murder. Along with the Finance Committee, Fellowship Committee, and Youth Committee my home church formed a “Nigger” Committee, composed of the biggest and meanest men in the church, who met each Sunday on the steps of the church with one job and only one job: while the pastor stood in the pulpit preaching about a God who loved everyone, a certain race of people must NEVER, EVER get through that door! Where had all the prophets gone?

In the early 1960s fewer than 2% of Mississippi’s African-American population were registered to vote. Some counties did not have a single registered African-American voter! Yet White supremacy and segregation, twin Southern traditions proudly inherited by each new generation through paternal bloodlines and ingested through mother’s milk, were being threatened. “Ohhh, dat Gospel train’s a comin’; I hear dat whistle blowin’.”

The moment a Southerner surrenders his life to Christ for a lifetime of Christian ministry a crisis strikes. In the area of race relations shall he follow a course of continuation or compensation? Shall he follow Christ or culture? Will there be a transfer of allegiance? Whom shall one now seek to please, earthly father or heavenly Father? Shall the minister follow society or Scripture? Which will it be: family or faith? The choice is hard. Religion would be much easier if ethics were not involved.

Kay and I concluded there was no choice after all. Either Christ was Lord or He wasn’t. Robert Frost’s poem, The Road Not Taken, expresses our own dilemma and decision:

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

and sorry I could not travel both

and be one traveler, long I stood

and looked down one as far as I could

to where it bent in the undergrowth;

I then took the other, as just as fair,

and having perhaps the better claim,

because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this one day with a sigh

somewhere ages and ages hence:

two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

and that has made all the difference.

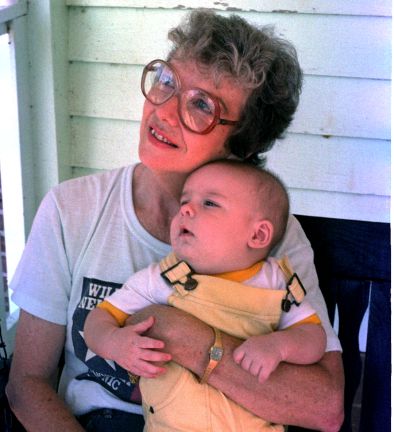

“The Road Taken” led us to minister in the ghettos of New Orleans in the 1970s while I was in seminary. Soon we had joined an African-American Church in the inner city as its only two white members. In time Kay was asked to serve as Sunday School Superintendent and I was invited to serve as Associate Pastor. Our families tried hard to understand our calling to minister in this setting, and I believe they were successful in doing so. Their love and support blessed us.

When my ordination was scheduled in Kay’s home church in the Mississippi Delta, the church fellowship and our families seemed pleased. When we revealed, however, that we wanted our Pastor, the Reverend Andrew W. Gilmore of Christian Love Missionary Baptist Church in New Orleans to preach my ordination sermon, celebration turned into chaos. A “Negro” preach in the pulpit of an all-white Mississippi Delta church? In the very town in which the White Citizen’s Council was formed? And wouldn’t other “Negroes” want to make the trip from New Orleans as well?

Although my ordination in Roundaway Baptist Church in Sunflower County, Mississippi created no small crisis, we remain very proud of the way in which the Deacons and the church membership responded to the collision of segregation and Scripture. When Kay’s father, a deacon in the church, delivered a passionate appeal to the church on behalf of right, the church followed the leadership of the Holy Spirit beautifully. The ordination service provided a glimpse of God’s True Church where all believers are one in Christ Jesus.

We could not have known what awaited us in our first pastorate on the Mississippi-Louisiana State Line. Rather than reveal the name of the church I prefer the pseudonym “Southern Baptist Church.” Moreover all names are fictitious except in cases where a person lines up on the side of right. I am proud to make known the identities of the faithful.

“Are you going to Homecoming this weekend?” I asked Doug Taylor one Tuesday afternoon in October of 1979, as we walked across the campus of the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. Doug and I had graduated from Mississippi College, he in 1978 and I in 1975. “I’d love to, but I don’t have a car,” he lamented. “Hey, that’s no problem,” I said. “Kay and I are going and you are more than welcome to ride with us.”

“For real?” he asked. “Absolutely!” I said. And so the drama began innocently enough.

Kay and I planned to drive from New Orleans to Clinton, Mississippi, Friday afternoon, attend homecoming festivities at the college Saturday, then motor Saturday night to the church field where I served as Pastor. Sunday we would worship morning and evening, then return to New Orleans late Sunday night. We never even thought about the obvious. Then it hit me! “Hun,” I said, “I never once thought about this, but Doug is black and Southern Baptist Church is white. We’ve got a problem.”

“I never thought about it either,” she said, “what are we going to do?” “Well, maybe this is what God wants, even though we didn’t think about what we were doing,” I mused. “Let’s talk to Doug, explain the situation, pray about it for a couple of days, and see what we think we should do,” I suggested.

“Doug, I’ve got to explain something to you,” I began. With that I told him that a black person had never, ever been in the church, not even to cook or clean, and that the church sat in the heart of Klan territory, but that the invitation was still on the table. We agreed to pray. Thursday evening the three of us met in our home to finalize our plans according to God’s guidance through prayer. One by one we reported that our sense was “All Systems Go!” We had not intentionally plotted to integrate Southern Baptist Church. Despite our naivete, or maybe because of it, we felt providentially chosen by God for this historical act. If it is possible for fear and peace to coexist, those two polar neighbors seemed to find a home in our hearts.

Sunday morning arrived. Doug, Kay, and I, along with Eric Holleyman, our Associate Pastor for Music and Youth, prayed together at the parsonage then drove to the church. Word traveled fast. As soon as Sunday worship concluded, Sammy Wilson ran up to me and exploded, “Ed Earl wants to see you right now! He said to tell you to get your *^%#! over to his house the minute church is out!”

Ed Earl was a church member who attended church every leap year. I suspected he was a Klansman, but I had no way of knowing. In order to present the false impression that I was not frightened, I ate Sunday lunch first rather than rush right over. Eric insisted on going with me. When we arrived at Ed Earl’s, Jimmie Lou met us at the door and ushered us into the room where Ed Earl sat waiting. Jimmie Lou excused herself, closing the door behind her. Ed Earl said nothing for the longest. Then he began.

“Got a little visit this mornin’,” he said. “The boys came by, tearin’ into my driveway in their pick-up trucks, slingin’ gravel everywhere, blowin’ their horns, slammin’ on brakes, throwin’ rocks, and hollerin’—‘Ed Earl, git out here quick!’ Well, I went outside and said, ‘What’re you boys up to?’ They said, ‘Git in the truck, Ed Earl!’ I said, ‘Where you boys goin’?’ They said, ‘Git in the *%^# truck, Ed Earl! We’re goin’ to git us a nigger ’n a preacher!’

Then they told me it was you! I was so mad I could *%^#! But I told ‘em, ‘I’m gonna have to ask you boys to turn around and go back home.’ ‘What!’ they said. ‘You heard me boys. Lemme handle this one; I owe that preacher one; he’s taken up a lot o’ time with my boy, huntin’, playin’ ball. But I tell you what I’m gonna do. If it ever happens again, you won’t be pickin’ me up. I’ll be pickin’ you up! Now go on home. I’ll take care of this one.”

Ed Earl paused as he spoke—eyes watering, face beet red—then he looked me square in the eye, voice quivering, and threatened, “If it ever happens again . . . .”

Ed Earl never finished his sentence. He didn’t have to. I understood. My life was being threatened. “Ed Earl,” I managed meekly, “what are you asking me to do? To stand in that pulpit and preach about a God who loves everybody, but put a sign in front of the church saying ‘No Negroes Allowed?’ I can’t do that, Ed Earl. You’ve gotta decide what you’ve gotta do; I’ve gotta do what God tells me to do.” Ed Earl stared daggers through me. I felt I was peering into the face of death.

“It better not happen again!” he warned. “Does tonight count?” I asked. “Because I can’t tell a man who wants to worship God that he can’t come in the church. I’m not going to do that, Ed Earl.”

That evening before Doug, Kay, Eric, and I went to church we prayed, placing ourselves and the witness of that day in God’s hands. The evening crowd nearly filled the sanctuary, which was unusual. Standing before the congregation I reminded the worshipers that we had the right to choose the color of carpet for the church, but not the color of skin of worshipers. God had already decided that.

The less I said that night and the more God said the better things would go, I felt. Two biblical texts stuck in my mind: Joshua 24:15, which reads, “Choose you this day whom you will serve . . . , but as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord,” and 1 John 4:20 which warns, “If some one says, ‘I love God,’ and hates his brother, he is a liar.”

Standing floor level in front of the Lord’s Supper Table, upon which rested a suitcase-size Pulpit Bible, I turned, took the massive Bible, held it before the people, and charged, “Let us choose this day whom we will serve, Christ or culture. But let us be truthful. Let us have a Bible that we will live by. If you choose culture over Christ this day then I want you to come tear out this page that says we are to love one another, wad it up, and throw it away. If you choose to please your earthly father instead of your heavenly Father then come rip out this page that reads, ‘If some one says, I love God, and hates his brother, he is a liar.’ Let’s tear out and throw away all these pages we don’t want in our Bible. Let’s not be hypocrites. Let’s make a Bible we will live by.”

The sanctuary fell silent. “On the other hand,” I continued, “if this day you choose Christ over culture, I want you to come up here, take this pulpit Bible from me, and seal your commitment by reading from this Book before God and this assembly. Choose you this day!”

With the charge complete, I sealed my own commitment to the Lordship of Jesus Christ by reading from 1 John 4:7-8: “Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God, and every one who loves is born of God and knows God. The one who does not love does not know God, for God is love.” Eric Holleyman walked forward, took the Bible from me, faced the congregation and began reading where I had stopped: “By this the love of God was manifested in us . . . .” He read until Kay marched down the aisle, received the huge Book from Eric, and read, “Beloved, if God so loved us, we also ought to love one another.” Doug Taylor followed Kay. What a sight to behold it was! A black man holding the pulpit Bible of Southern Baptist Church in 1979! “And this commandment we have from Him, that the one who loves God should love his brother also,” this child of God read.

Revival broke out! ‘Miss’ Elsie Smith, one of our oldest widows, waddled forward and whispered in my ear, “Hun, I can’t read; would you read for me?” Together we held the Bible as I read for her. Others came. Soon almost everyone had publicly declared their intentions to live according to God’s will rather than man’s ways.

Leon Johnson was the exception. Leon sat frozen on the back pew, a mask of hatred glued to his face. He rushed out into the night.

After everyone had left for the night, Kay, Doug, Eric, and I turned out the lights, locked up the church, and headed out the door. Before walking out into the dark southern night, not knowing what or who might be awaiting us, we prayed.

Relief! Crickets, not Klan, greeted us as we opened the door. We drove to the parsonage to change into casual clothes for the drive back to New Orleans. As we prepared to leave the parsonage, fear gripped us. Who would be waiting outside in the dark? We prayed together, then opened the door. Nothing! Praise the Lord, no one was there! Driving down the deserted country roads which carried us toward I-55 miles away, our pulse quickened each time headlights hit our rear view mirror. Not until we drove into the bright lights of New Orleans did we feel safe.

When Eric, Kay, and I returned to the church field the next weekend we were shocked! Southern Baptist Church was a ghost town! The Klan had reached the members during the week. Almost no one dared attend church! Kenny Joe Cobb, the leading tither in the church, said he’d never give another nickel as long as I was pastor of the church. Elmer Newton, the oldest deacon in the church swore he’d never darken the door of the church as long as I was there. Despite our best efforts to shepherd the flock, visit the church families, preach the Word, love the unlovely, visit the sick, the widows, and those confined to nursing homes, and pray, pray, pray, nothing worked. Our days at Southern Baptist Church were numbered.

After doing everything we could to re-build the fellowship, unsuccessfully, I resigned as Pastor of Southern Baptist Church. Six months of painful struggle came to an end. Kay and I simply felt that if the church were ever going to have a chance to heal and grow again, we needed to go. The loving thing for us to do was to leave.

I am told the first question the Pastor Search Committee asked each new pastoral candidate was, “What do you think of niggers in the church?”

And so it was in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

But this is a new millennium.

Isn’t it?

Updated Friday, March 25, 2005

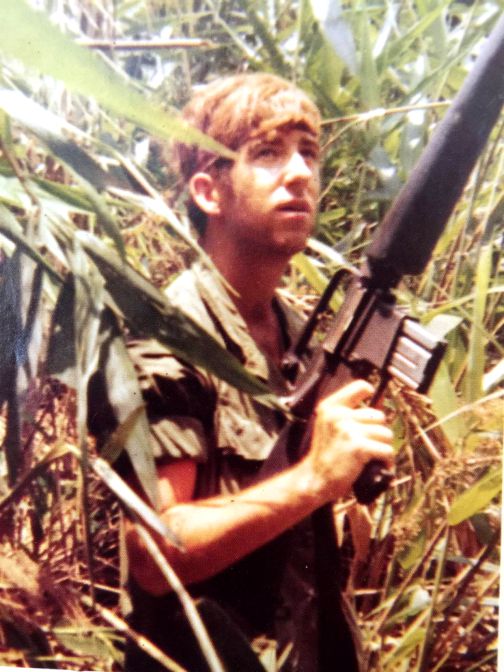

Dr. J. Randall O’Brien is the recently retired President of Carson-Newman University in Jefferson City, Tennessee. Previously the executive vice president, provost, professor of religion and visiting law professor at Baylor University, the McComb, Mississippi native is a graduate of Yale Divinity School, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, and Mississippi College. He has also held appointments as a Research Scholar at Yale, and Fellow at Oxford.

Other Porchscene articles by Dr. O’Brien include:

http://porchscene.com/2017/10/17/a-bronze-star-for-brenda/

http://porchscene.com/2017/09/26/dark-rains-gonna-fall/ http://porchscene.com/2017/08/22/3rd-civil-war/

The Gold Embossed Funeral Invitation

Photo: Deborah Fagan Carpenter

Like this:

Like Loading...